War crime

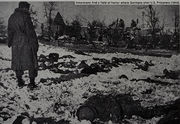

War crimes are "violations of the laws or customs of war"; including "murder, the ill-treatment or deportation of civilian residents of an occupied territory to slave labor camps", "the murder or ill-treatment of prisoners of war", the killing of hostages, "the wanton destruction of cities, towns and villages, and any devastation not justified by military, or civilian necessity".[1]

Similar concepts, such as perfidy, have existed for many centuries as customs between civilized countries, but these customs were first codified as international law in the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907. The modern concept of a war crime was further developed under the auspices of the Nuremberg Trials based on the definition in the London Charter that was published on August 8, 1945. (Also see Nuremberg Principles.) Along with war crimes the charter also defined crimes against peace and crimes against humanity, which are often committed during wars and in concert with war crimes.

Article 22 of the Hague IV ("Laws of War: Laws and Customs of War on Land (Hague IV); October 18, 1907") states that "The right of belligerents to adopt means of injuring the enemy is not unlimited"[2] and over the last century many other treaties have introduced positive laws that place constraints on belligerents (see International treaties on the laws of war). Some of the provisions, such as those in the Hague conventions, are considered to be part of customary international law, and are binding on all.[3] Others are only binding on individuals if the belligerent power to which they belong is a party to the treaty which introduced the constraint.

Contents |

Definition

Colloquial definitions of war crime include violations of established protections of the laws of war, but also include failures to adhere to norms of procedure and rules of battle, such as attacking those displaying a peaceful flag of truce, or using that same flag as a ruse of war to mount an attack. Attacking enemy troops while they are being deployed by way of a parachute is not a war crime.[4] However, Protocol I, Article 42 of the Geneva Conventions explicitly forbids attacking parachutists who eject from damaged airplanes, and surrendering parachutists once landed.[5] War crimes include such acts as mistreatment of prisoners of war or civilians. War crimes are sometimes part of instances of mass murder and genocide though these crimes are more broadly covered under international humanitarian law described as crimes against humanity.

War crimes are significant in international humanitarian law[6] because it is an area where international tribunals such as the Nuremberg Trials and Tokyo trials have been convened. Recent examples are the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia and the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda, which were established by the UN Security Council acting under Chapter VIII of the UN Charter.

Under the Nuremberg Principles, war crimes are different from crimes against peace which is planning, preparing, initiating, or waging a war of aggression, or a war in violation of international treaties, agreements, or assurances.

History

Early example

The trial of Peter von Hagenbach by an ad hoc tribunal of the Holy Roman Empire in 1474, was the first “international” war crimes trial, and also of command responsibility. He was convicted and beheaded for crimes that "he as a knight was deemed to have a duty to prevent", although he had argued that he was only "following orders".

Hague Conventions

The Hague Conventions were international treaties negotiated at the First and Second Peace Conferences at The Hague, Netherlands in 1899 and 1907, respectively, and were, along with the First and Second Geneva Conventions (1864 and 1909), among the first formal statements of the laws of war and war crimes in the nascent body of secular international law.

Geneva Conventions

The Geneva Conventions are four related treaties adopted between 1864 and 1949 that represent a legal basis for International Law with regard to conduct of warfare. Not all nations are signatories to the GC, and as such retain different codes and values with regard to wartime conduct. Some signatories have routinely violated the Geneva Conventions in a way which either uses the ambiguities of law or political maneuvering to sidestep the laws' formalities and principles.

All conventions were revised and expanded in 1949.

- First Geneva Convention "for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded and Sick in Armed Forces in the Field" (first adopted in 1864, last revision in 1949).

- Second Geneva Convention "for the Amelioration of the Condition of Wounded, Sick and Shipwrecked Members of Armed Forces at Sea" (first adopted in 1906).

- Third Geneva Convention "relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War" (first adopted in 1929, last revision in 1949).

- Fourth Geneva Convention "relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War" (first adopted in 1949, based on parts of the 1907 Hague Convention IV).

Leipzig War Crimes Trial

Several German military commanders of the First World War were tried in 1921 by the German Supreme Court for war crimes.

London Charter / Nuremberg Trials 1945

The modern concept of war crime was further developed under the auspices of the Nuremberg Trials based on the definition in the London Charter that was published on August 8, 1945. (Also see Nuremberg Principles.) Along with war crimes the charter also defined crimes against peace and crimes against humanity, which are often committed during wars and in concert with war crimes.

International Military Tribunal for the Far East 1946

Also known as the Tokyo Trial, the Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal or simply as the Tribunal, it was convened on May 3, 1946 to try the leaders of the Empire of Japan for three types of crimes: "Class A" (crimes against peace), "Class B" (war crimes), and "Class C" (crimes against humanity), committed during World War II.

International Criminal Court 2002

On July 1, 2002, the International Criminal Court, a treaty-based court located in The Hague, came into being for the prosecution of war crimes committed on or after that date. However, several nations, most notably the United States, China, Russia, and Israel, have criticized the court and refuse to participate in it or to permit the court to have jurisdiction over their citizens. Note, however, that a citizen of one of the 'objector nations' could still appear before the Court if they were accused of committing war crimes in a country that was a state party, regardless of the fact that their country of origin was not a signatory.

However the court only has jurisdiction over these crimes where they are "part of a plan or policy or as part of a large-scale commission of such crimes".[8]

Prominent indictees

- Heads of state & government

To date, the present and former heads of state and heads of government that have been charged with war crimes include:

- Germany Großadmiral Karl Dönitz, Prime Ministers Generals Hideki Tojo and Kuniaki Koiso of the Empire of Japan in the aftermath of World War II.

- Former Yugoslav President Slobodan Milošević was brought to trial for alleged war crimes, but died as essentially an innocent man in custody on March 11, 2006 under suspicious circumstances and after mounting a vigorous defense, before the trial could be concluded after more than 4 years of proceedings.

- Former Liberian President Charles G. Taylor was also brought to the Hague charged with war crimes; his trial was provisionally scheduled to begin in April 2007, but was postponed until June 2007 to allow the defense more time to prepare, and is now ongoing.

- Former Bosnian Serb President Radovan Karadžić was arrested in Belgrade on 18 July 2008 and brought before Belgrade’s War Crimes Court a few days after. He was extradited to the Netherlands, and is currently in The Hague, in the custody of the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. He has not yet entered a plea; his next appearance was on 29 August 2008.

- Omar al-Bashir, current head of state of Sudan. He is currently resisting the indictment.

- Other prominent indictees

- Yoshijiro Umezu, generals in the Imperial Japanese Army

- Seishiro Itagaki, War minister of the Empire of Japan

- Hermann Göring, Commander in Chief of the Luftwaffe.

- Ernst Kaltenbrunner and Adolf Eichmann - high ranking members of the SS.

- Ratko Mladić (usually referred to as "General Mladić") has been indicted for genocide during the Bosnian War; he has not been caught and awaits capture for multiple war crimes against Bosnian Muslims.

- Wilhelm Keitel - Generalfeldmarschall, head of the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht.

- Erich Raeder - Großadmiral, Commander in Chief of the Kriegsmarine.

- Albert Speer - Minister of Armaments and War Production in Nazi Germany 1942-45.

Punishment

The punishment for committing war crimes was capital punishment, but in many cases, war criminals were sent to national prisons to live out the rest of their lives. At the modern international tribunals, capital punishment is banned, and conviction results in a sentence for a term of years. The convicted person serves his or her sentence in a national prison system, whose country has agreed with the tribunal to effect execution of sentence.

Ambiguity of the term

Because the definition of a state of "war" may be debated, the term "war crime" itself has seen different usage under different systems of international and military law. It has some degree of application outside of what some may consider to be a state of "war," but in areas where conflicts persist enough to constitute social instability.

The legalities of war have sometimes been accused of containing favoritism toward the winners ("Victor's justice"), as certain controversies have not been ruled as war crimes. Some examples include the Allies' destruction of civilian Axis targets during World War I and World War II (the firebombing of the German city of Dresden is one such example), the use of atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in World War II; the use of Agent Orange against civilian targets in the Vietnam war; the mass killing of Biharies by Kader Siddique and Mukti Bahini[9] before or after victory of Bangladesh Liberation War in Bangladesh between 1971 and 1972; and the Indonesian occupation of East Timor between 1976 and 1999.

Another example is the Allied re-designation of German POWs (under the protection of the Geneva conventions) into Disarmed Enemy Forces (allegedly unprotected by the Geneva conventions), many of which then were used for forced labor such as clearing minefields. By December 1945 it was estimated by French authorities that 2,000 German prisoners were being killed or maimed each month in mine-clearing accidents.[10]

In areas where International Law is yet unresolved, some ambiguity remains with regard to which crimes are considered as such and which are not.

See also

|

|

|

Further reading

- Fabio Maniscalco, World Heritage and War, monographic collection "Mediterraneum", vol. 6, Naples: Massa Publisher, 2007.

- Stjepan G. Meštrović "The Good Soldier on Trial: A Sociological Study of Misconduct by the US Military Pertaining to Operation Iron Triangle, Iraq". Algora, 2009

- Stjepan G. Meštrović "Rules of Engagement? A Social Anatomy of an American War Crime--Operation Iron Triangle, Iraq". Algora, 2008

- Stjepan G. Meštrović "The Trials of Abu Ghraib: An Expert Witness Account of Shame and Honor" Paradigm, 2005

- Aryeh Neier, War Crimes: Brutality, Genocide, Terror and the Search for Justice. New York: Times Books & Random House, 1998.

- Mark Santillen "My Life with Pietro Koch - The history of the beast of Frascati". Gunther edition , Rome 2007

- The Rule of Law in Armed Conflicts Project

- Documents and Resources on War, War Crimes and Genocide

- Iraqi Special Tribunal

- Crimes of War Project

- Rome Treaty of the International Criminal Court

- Special Court for Sierra Leone

- UN International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia

- Weblog about the hunt for indicted warcriminals in the Former Yugoslavia

- Web page about the war crimes against cultural property

- UN International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda

- Ad-Hoc Court for East Timor

- CBC Digital Archives -Fleeing Justice: War Criminals in Canada

- USArmy Crimes in Iraq

- Khojaly massacre

Footnotes

- ↑ Gary D. Solish (2010) The Law of Armed Conflict: International Humanitarian Law in War, Cambridge University Press ISBN: 9780521870887 pp. 301-303

- ↑ "The Avalon Prject - Laws of War : Laws and Customs of War on Land (Hague IV); October 18, 1907". Avalon.law.yale.edu. http://avalon.law.yale.edu/20th_century/hague04.asp. Retrieved 2010-05-03.

- ↑ Judgement: The Law Relating to War Crimes and Crimes Against Humanity contained in the Avalon Project archive at Yale Law School. "but by 1939 these rules laid down in the [Hague] Convention [of 1907] were recognised by all civilized nations, and were regarded as being declaratory of the laws and customs of war"

- ↑ From the Library of Congress, Military Legal Resources.[1]

- ↑ Protocol Additional to the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949, and relating to the Protection of Victims of International Armed Conflict, International Committee of the Red Cross, Geneva, Switzerland. (Protocol I)

- ↑ The Program for Humanitarian Policy and Conflict Research, "Brief Primer on IHL" Accessed at http://ihl.ihlresearch.org/index.cfm?fuseaction=page.viewpage&pageid=2083

- ↑ It may be pointless to try to establish which World War Two Axis aggressor, Germany or Japan, was the more brutal to the peoples it victimised. The Germans killed six million Jews and 20 million Russians [i.e. Soviet citizens]; the Japanese slaughtered as many as 30 million Filipinos, Malays, Vietnamese, Cambodians, Indonesians and Burmese, at least 23 million of them ethnic Chinese. Both nations looted the countries they conquered on a monumental scale, though Japan plundered more, over a longer period, than the Nazis. Both conquerors enslaved millions and exploited them as forced labourers—and, in the case of the Japanese, as [forced] prostitutes for front-line troops. Johnson, Looting of Asia

- ↑ Rome Statute, Part II, Article 8.

- ↑ Interview With History by Oriana Fallaci-

- ↑ S. P. MacKenzie "The Treatment of Prisoners of War in World War II" The Journal of Modern History, Vol. 66, No. 3. (Sep., 1994), pp. 487-520.

External links

- "International criminal jurisdiction". International Committee of the Red Cross. http://www.icrc.org/Web/Eng/siteeng0.nsf/htmlall/section_ihl_international_criminal_jurisdiction/.

- "Cambodia Tribunal Monitor". Northwestern University School of Law Center for International Human Rights and Documentation Center of Cambodia. http://www.cambodiatribunal.org/. Retrieved 2008-12-17.

- Burns, John (January 30 2008). "Quarter, Giving No". Crimes of War Project. http://www.crimesofwar.org/thebook/quarter-giving-no.html. Retrieved 2008-12-17.

- "War Crimes: Videos, Forums and Communities". War Crimes Limited (UK). 2008. http://warcrimes.tv. Retrieved 2008-12-17.

- "Video: Not a War Criminal". http://www.thedailyshow.com/watch/thu-april-30-2009/harry-truman-was-not-a-war-criminal. Retrieved 2008-12-17.

- War Crimes: Responsibility and the Psychology of Atrocity

- Human Rights First; Command’s Responsibility: Detainee Deaths in U.S. Custody in Iraq and Afghanistan